Frances Tustin’s therapeutic approach to children with autism was based on her training as a child psychotherapist in the school of Melanie Klein. Technically, this involves providing the child with toys that are suited to eliciting play about his or her inner world, such as small dolls, tame and wild animals, a dolls house, cars, bricks, drawing materials, and so on. The therapist carefully observes the child’s play and other kinds of behaviour, as well as the emotional atmosphere between herself and the child. Based on this tempered by a fair amount of intuition and experience, she makes imaginative comments about how the child appears to be experiencing the relationship with her, which is assumed to derive from his internal world and ideas about how people are likely to behave.

This helps him to feel understood and accepted, and promotes growth. He can develop new ways of relating to other people, instead of remaining stuck in habitual patterns that may not be realistic or adaptive.

Children with autism do not talk or play until they are getting better, and their sensory experience can be very different from that of the rest of us. At the same time, and above all, they are people in their own right, with emotions that need a response just as other children’s do. This can be difficult for their caretakers – and their therapists – because the particular way they express themselves is so often difficult to decode. Frances Tustin was anything but doctrinaire, and remained keenly interested in knowledge from any source that could help her better to empathise with the children she treated. She had a particular gift for feeling her way into autistic children’s experience, especially their bodily experience. When they recovered and began to speak, they were able to describe seemingly bizarre states, such as the feeling of losing parts of their body. In recent years, many of her formulations have been confirmed by the first-person accounts of people with autism.

Earlier in treatment, when her patients could not yet speak or play, it was a matter of gauging their feelings from the way they used their bodies. This requires the therapist to take the emotional context into account, and to judge by the child’s response whether she is on the right track. For instance, children who excitedly spin around may be obliterating their awareness of being separate, or they may be trying to heighten their proprioceptive awareness of all the different parts of their body. In Tustin’s opinion, children with autism begin by relating to the therapist as a function, rather than as a separate person; it is not until later that the infantile transference developes. The ‘infantile transference’ is the process whereby feelings from babyhood are re-experienced vis-à-vis the therapist. Once this process is set in motion, the therapist can verbalise it, which helps the child to move on from positions he had become stuck in and to relinquish the wayward and often secretive stereotypical practices that had been getting in the way of his development and interfering with human relations.

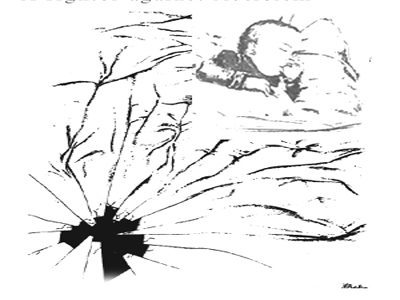

Tustin adopted a more active technique with her autistic patients than is typical of child psychotherapy with other kinds of children: for example, she might gently hold a child’s hands, and explain, ‘Tustin can hold the upset’. She was empathetic and compassionate, but totally unsentimental, and she thought that excessive indulgence was as bad for children with autism as for any other child. At the same time, she was keenly aware of the vulnerability that made their self-protective manoeuvres necessary, and warned against the dangers of interfering with these prematurely or clumsily. Reading the case reports of her patients – John of the black hole in his mouth, David of the suit of armour, Peter who mused on the difference between thought and sensation – is an object lesson in how a therapist can reach imaginatively into a different world and make it possible for the child to risk joining ours.