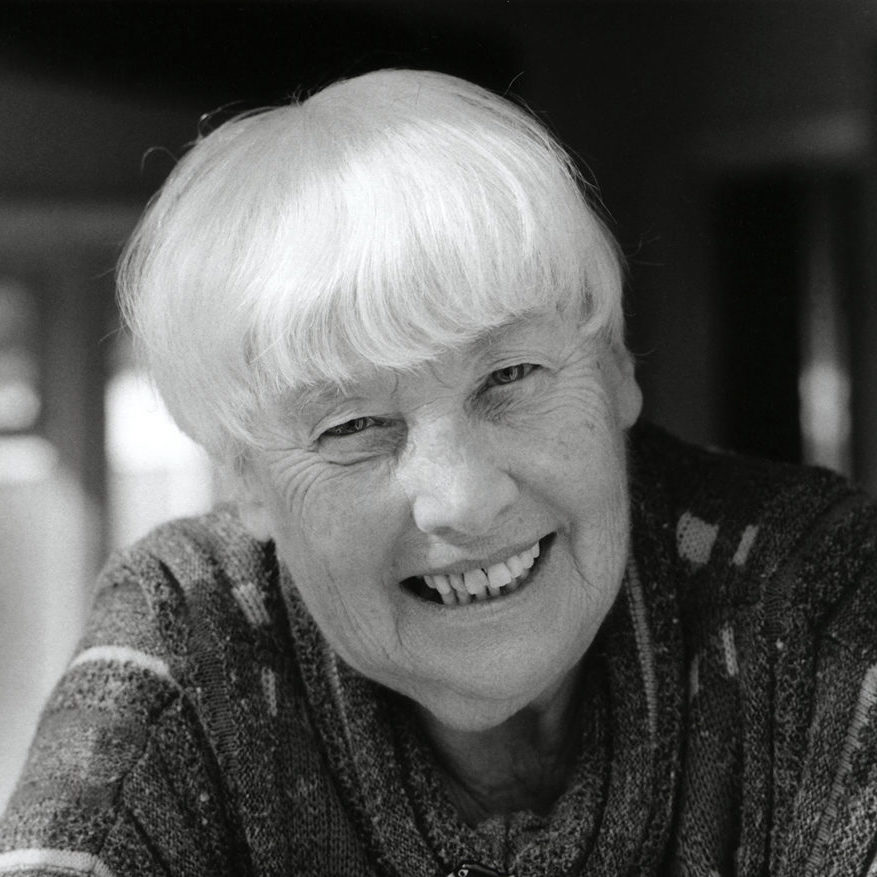

Frances Tustin was a renowned child psychotherapist pioneering on the frontiers of the psychoanalytic understanding and treatment of autistic states in children and adults since the early 1950’s. She was born in the North of England in 1913 and, after obtaining her High School Certificate (equivalent to the Baccalaureate degree) decided to become a teacher. To this end, she trained at Whiteland’s Church of England College. After her graduation, she worked as a teacher there for several years.

Tustin first became introduced to psychoanalysis while attending the course by Susan Isaacs on child development at the University of London in 1943. Inspired to train as a child psychotherapist, her plans were interrupted by WWII. Back on track once the war had ended, in 1950 she registered for the child psychotherapy training at the Tavistock Clinic, which had been founded in 1948 by Esther Bick upon the request of Dr. John Bowlby, who was the Chair of the Tavistock at that time.

Tustin was trained as a child psychotherapist from 1950 to 1953. In the context of her training, she began her analysis (which was to span 16 years) with W.R. Bion. In the mid 1950’s she had the opportunity to go to the United States for a year with her husband, Arnold, who had been invited, as a visiting lecturer in residence, by the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Tustin took advantage of that stay in The USA to work at the James Jackson Putnam Center headed up by the widow of well-known analyst Otto Rank. At that center, autistic children were treated behaviorally, by today’s standards. This was Tustin’s first contact with these atypical children. Along with the work she was assigned, in her free time she engaged in what was to become an energetic study of the records on each atypical child seen at The Putnam Center to that date. This research fueled her interest and curiosity as she began what was to be a lifelong process of understanding the autistic child.

Upon returning to London, Tustin sought to work with autistic children utilizing the Kleinian technique of child psychoanalysis that she had learned in her Tavistock training with Esther Bick, Donald Meltzer, Herbert Rosenfeld and Martha Harris among others. Dr. Mildred Creak — a renowned child psychiatrist at Great Ormond Street Hospital, who specialized in the diagnosis of autistic and psychotic children — referred children to Mrs. Tustin for treatment, especially those in whom autism was considered to be predominately psychogenic in nature.

It was with one child, whom she called “John”, that Tustin discovered the core problematic in this type of autism: a lack of continuity “mouth-tongue-nipple-breast”, due to the child’s premature awareness of his separateness from the maternal nipple-breast. Tustin found that the awareness of the experience of such discontinuity in an infant who has yet to acquire the capacity to symbolize the absence and the absent object, is that of a ‘black hole’ filled with dangerous objects. John called this a ‘black hole with a nasty prick’. Tustin learned from her work with John that, in order to protect himself against that traumatic experience of annihilation, the child attempts to freeze time and and to nullify such dangerous spaces, into which he might endlessly fall, by enclosing himself within a world of self-made soothing sensations of impermeability and changelessness. Unfortunately these autistic maneuvers profoundly hinder the child’s social and cognitive development.

After writing about her findings in several papers, published in the sixties, and with these clinically rooted discoveries firmly articulated in her mind, Tustin published her first book Autism and Childhood Psychosis in 1972. She gave numerous lectures in Great Britain and abroad and began supervising cases of autistic children being treated throughout Great Britain and Europe. By 1990 Tustin had published three more books, which were translated in several languages. She had written and published, in the most prestigious journals, many articles about her findings and she welcomed students from all over the world to supervise their psychoanalytic treatment of autistic children. Tustin often used evocative imagery, one feature of her writing that made it so accessible, and she often turned to the poets to help her to convey the atmosphere of what she felt to be the sensation-dominated world of autistic children. Poetry is rooted in those primordial states, and poetic language — with its rhythmical and melodious flow and its freedom from grammatical and syntactic constraints — appeared to her to reach down to those deepest levels.

Tustin was a tireless and prolific contributor in the field, publishing her last paper just weeks prior to the end of her life at the age of 81.

A prominent member of The Association of Child Psychotherapists in Great Britain and an Honorary Member of the Psychoanalytic Center of California (PCC), Mrs. Tustin was a dedicated and inspiring teacher and an advocate for autistic children and their parents. In all of her human interactions, she exhibited an overflowing sensitivity, a positive sensuality and a musical voice with a vivid vocabulary. Her unparalleled expressiveness of gesture, her effervescent laughter, her immense emotional vibrancy and her profound capacity for containment (always articulated in a truly poetic way) were qualities that aided her in the discovery, comprehension and treatment of autistic children.

In turn, those children with whom she worked helped her to deepen her passionate explorations into the world of infantile autism. It is certainly noteworthy that her contribution to the development of psychoanalysis was recognized in 1984 by the British Psycho-Analytical Society, which awarded her the rare status of Honorary Affiliate Member.

Although she was recognized, acknowledged and honored by many institutions, as Donald Meltzer wrote. “Tustin’s independence from organized schools and their prescribed thinking made her an observer of peculiar freedom and therapeutic effectiveness.” In this spirit, Tustin addressed childhood psychoses in counter distinction to autism, clarifying and deepening the principals advanced by Melanie Klein and her followers. Through her work with children and adolescents with various pathological structures Tustin’s discovery — that autistic trends are frequently found in the so-called symbiotic psychoses or confusional psychoses – made her ever more aware of what she called ‘autistic enclaves’ in a variety of child and adult patients who seek psychotherapy. As Andre Green wrote, “Tustin influenced not only those interested in the specific problems of autistic states, but also those who shared an intuition that autism could play the role of a new paradigm for the study of the mind.” It is certainly no wonder that, more than two decades after her death, Tustin’s invaluable body of work remains alive and generative all over the world today.

Treatment of Autistic Spectrum Disorders

Frances Tustin’s therapeutic approach to the treatment of children with autism was based upon her training as a child psychotherapist at The Tavistock Clinic in the tradition of Melanie Klein. Technically, this approach involves providing the child with simple toys that are suited to eliciting play that aid the child in communicating aspects of his or her inner world. These toys may include small dolls, tame and wild animals, a dolls house, construction materials, cars, blocks, drawing materials, and so on. The therapist carefully observes the child’s play and other kinds of behaviour, as well as the emotional atmosphere that is created between his or herself and the child. Based on this template and tempered by a fair amount of intuition and experience, the therapist makes imaginative conjectures about how the child appears to be experiencing the relationship with the therapist, which is assumed to derive from the child’s internal world and unconcious fantasy life and ideas about how people are likely to behave. This helps him or her to feel understood and accepted, and promotes growth. The child can develop new ways of relating to other people, instead of remaining stuck in habitual patterns that may not be realistic or adaptive.

Children with autism do not talk or play until they are getting better, and their sensory experience can be very different from that of the rest of us. At the same time, and above all, they are people in their own right, with emotions that need a response just as other children do. This can be difficult for their caretakers – and their therapists – because the particular way they express themselves is so often difficult to decode. Frances Tustin was anything but doctrinaire, and remained keenly interested in knowledge from any source that could help her to better empathise with the children she treated. She had a particular gift for feeling her way into autistic children’s experience, especially their bodily experience. When they recovered and began to speak, they were able to describe seemingly bizarre states, such as the feeling of losing parts of their body. In recent years, many of her formulations have been confirmed by the first-person accounts of people with autism.

Earlier in treatment, when her patients could not yet speak or play, it was a matter of gauging their feelings from the way they used their bodies. This requires the therapist to take the emotional context into account, and to judge by the child’s response whether she is on the right track. For instance, children who excitedly spin around may be obliterating their awareness of being separate, or they may be trying to heighten their proprioceptive awareness of all the different parts of their body. In Tustin’s opinion, children with autism begin by relating to the therapist as a function, rather than as a separate person; it is not until later that the infantile transference developes. The ‘infantile transference’ is the process whereby feelings from babyhood are re-experienced vis-a-vis the therapist. Once this process is set in motion, the therapist can verbalise it, which helps the child to move on from positions he had become stuck in and to relinquish the wayward and often secretive stereotypical practices that had been getting in the way of his development and interfering with human relations.

Tustin adopted a more active technique with her autistic patients than is typical of child psychotherapy with other kinds of children: for example, she might gently hold a child’s hands, and explain, ‘Tustin can hold the upset’. She was empathetic and compassionate, but totally unsentimental, and she thought that excessive indulgence was as bad for children with autism as for any other child. At the same time, she was keenly aware of the vulnerability that made their self-protective manoeuvres necessary, and warned against the dangers of interfering with these prematurely or clumsily. Reading the case reports of her patients – John of the black hole in his mouth, David of the suit of armour, Peter who mused on the difference between thought and sensation – is an object lesson in how a therapist can reach imaginatively into a different world and make it possible for the child to risk joining ours.